Lebanon, once a prosperous country known in the 1950s and 1960s as the ‘Switzerland of the Middle East’, has been sinking into chaos, violence and terror for many decades. From 1975 to 1990, a bloody civil war raged in Lebanon. And since the end of this civil war, the Islamist terrorist organisation Hezbollah, founded in 1982, has been gaining more and more influence. The Islamists currently control large parts of the south of the country and also districts in the capital Beirut, which is why Israel has repeatedly carried out military operations on the ground and in the air to combat Hezbollah, which is financed by Iran. De facto, Lebanon is now a ‘failed state’ in which the government and the state executive powers have only very limited influence. State structures have largely eroded.

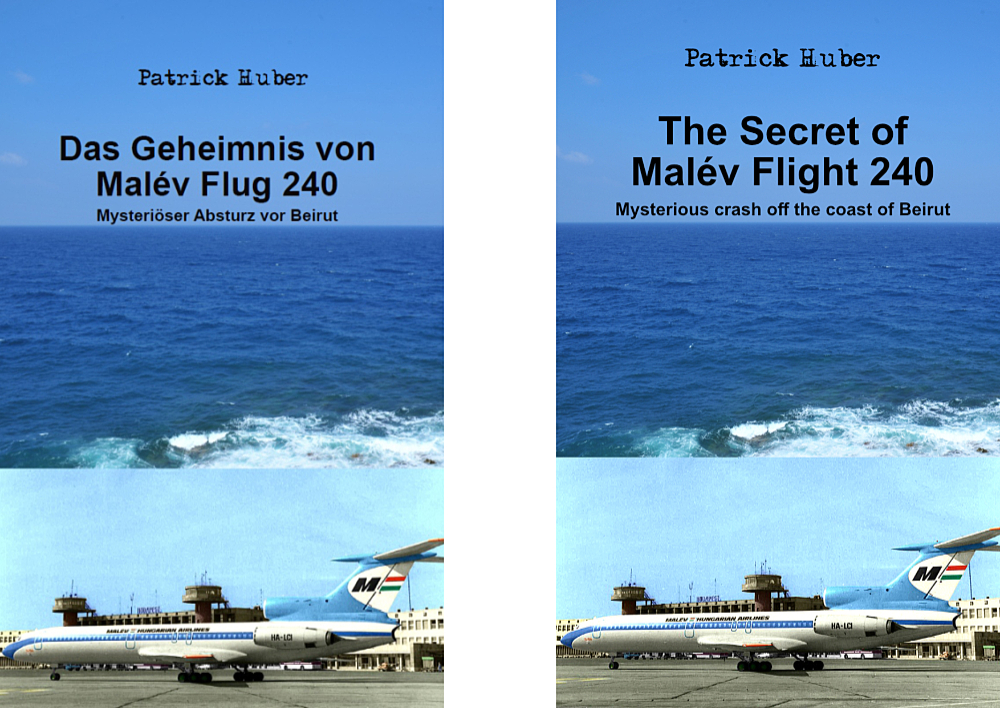

Against this backdrop, it is hardly surprising that an event as mysterious as it was dramatic, which took place exactly 50 years ago to the day, has been largely forgotten even in Hungary: the disappearance of a Hungarian Malév aircraft on 30 September 1975 shortly before landing in Beirut. There is strong evidence that the Tupolev Tu-154 was shot down by a fighter jet because members of the Palestinian terrorist organisation PLO (Palestine Liberal Organisation) were believed to be on board. This is the story of Malév Flight 240, about which I have also written the only German-language book to date. For my research, I even travelled to Budapest almost two years ago and conducted exclusive interviews with several eyewitnesses. My book ‘Das Geheimnis von Malév Flug 240: Mysteriöser Absturz vor Beirut’ (The Secret of Malév Flight 240: Mysterious Crash off Beirut) is available from the publisher's online shop, from any bookshop quoting the ISBN, and from various online booksellers in Germany and Austria (e.g. Thalia.at). Due to numerous requests in Hungary, the book was also published in English under the title ‘The Secret of Malév Flight 240 - Mysterious crash off the coast of Beirut’.

With the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, most airlines suspended their flights to the Lebanese capital Beirut. More than a dozen militias were involved in the conflict, including the Palestinian terrorist organisation PLO. The Lebanese capital Beirut, once known as the ‘Paris of the Middle East’, where the Gulf monarchies conducted their business and whose hotels had been frequented by famous actors, musicians and other celebrities, was reduced to rubble and ashes.

One of the few airlines still flying to Beirut was the Hungarian state-owned Malév. On 29 September 1975, another such flight was scheduled to take place, operated by a Tupolev Tu-154A with the registration number HA-LCI.

Highly qualified crew

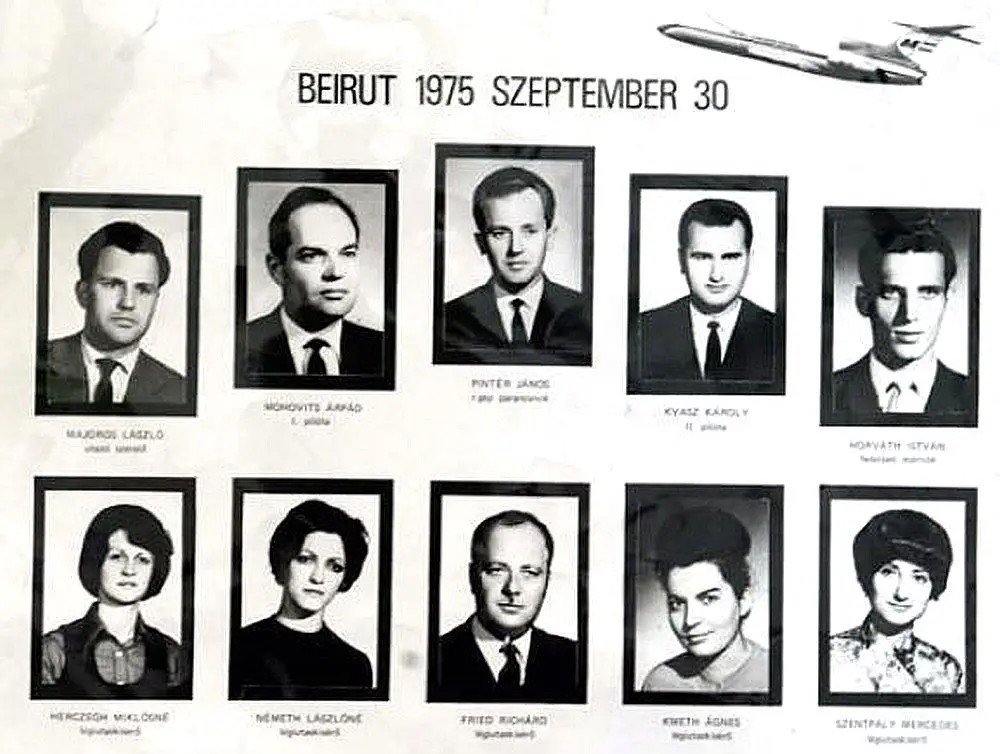

The crew was extremely experienced. It consisted of Captain János Pintér, co-pilot Károly Kvasz, flight engineer István Horváth, pilot/navigator Árpád Mohovits and an additional technician named László Majoros. The captain (42 years old) had around 3,700 hours of flying experience and was even qualified as an instructor for the Tu-154.

The first officer (36) had around 3,300 hours of experience. The flight engineer and the additional pilot were also not novices. The cabin crew on duty that day consisted of purser Richárd Fried (35) and flight attendants Ágnes Kmeth (39), Mercedesz Szentpály (25), Miklósné Herczeg (25) and Lászlóné Németh (24). Németh, the youngest member of the crew, had only been a stewardess with Malév for just under two weeks. It was one of her first international flights.

From today's perspective, it may seem incomprehensible that the crew did not object to this dangerous flight into a (civil) war zone, but one must take into account the circumstances of the time. In communist Hungary, it was not easy for pilots or flight attendants to refuse a flight assignment due to safety concerns – that would have meant the end of their careers and possibly even further disadvantages for the rest of their (professional) lives. Pilots and flight attendants in particular earned good money and saw something of the world, something that was denied to most Hungarian citizens at the time. It was a dream job that one did not easily put at risk.

Passengers from many countries

The assigned aircraft with the registration HA-LCI was just over two years old and in perfect technical condition. Produced and delivered as a basic Tu-154 model with the serial number (c/n) 74A053, the aircraft had previously flown for the Soviet Aeroflot (as CCCP-85053) and Egypt Air (as SU-AXG) before being modernised and converted to a Tu-154A. Malév then received the aircraft as HA-LCI and christened it with the Hungarian name ‘Ilona’, which translates as ‘the radiant one’. It was not until 20 June 1975, around three months before the fatal flight, that the Hungarian flag carrier put the jet into service. By 29 September 1975, the ‘Ilona’ had spent just under 1,200 hours in the air. It was therefore virtually new.

Dutch citizen Koop Van der Velde also wanted to fly to Beirut to take care of business matters and arrange the final move from Lebanon, where the family had been living, to the Netherlands. His wife and three daughters, including Francine, who was 15 at the time (she ran the website ‘The Lost Malev’ for many years, which appears to be currently offline) – she was available to me as an interview partner for my book about the ill-fated flight – were already safe in the Netherlands at that point. Mr Van der Velde had actually planned to fly from Amsterdam to Beirut with KLM, but because the Dutch airline had suspended the route due to the civil war that had been raging for five months, the businessman had to change his plans. He flew with KLM only as far as Budapest and wanted to continue on to Beirut with Malév from there.

High-ranking terrorists on the passenger list

They had booked their seats, and this circumstance is most likely the explanation for the shooting down of flight MA240, which experts consider highly probable, a high-ranking delegation of the Palestinian terrorist organisation PLO. The day before, on 28 September, this group had opened a kind of ‘embassy’, a so-called liaison office, in Budapest and was more or less openly supported by the Soviet Union and, on its instructions, by other socialist and communist states. At that time, Hungary was extremely anti-Israeli and supported the Palestinian agitation of terrorist Yasser Arafat, who had been PLO chairman since 1969. Fifty-three members of the PLO leadership, including Khaled al-Fahoum, who had founded the PLO together with Yasser Arafat and had been president of the ‘Palestinian parliament in exile’ since 1971, were booked on Flight 240, and special VIP check-in facilities had been arranged for these men at Budapest Airport that day – but the PLO members never showed up for check-in, instead travelling later by train from Budapest to Belgrade. Such last-minute changes to the PLO leadership's travel plans were quite common at the time, out of fear of attacks by the secret services, as I learned during my research for the book.

Illegal transport of military equipment highly probable

It is also known that a group of Finnish soldiers wanted to book tickets for this exact flight in mid-September, but were told by the Malév sales office that MA240 was already ‘fully booked’. This statement seems very strange, as even with the PLO delegation, there were just over 100 passengers booked, leaving a good 50 to 60 seats free in the cabin of the Tu-154A. The fact that Malév nevertheless did not want to sell any more seats was most likely due to the fact that the capacity was needed for additional cargo. According to Hungarian witnesses, boxes containing unknown cargo were demonstrably loaded into the fuselage of the ‘Ilona’ on 29 September.

Hungarian sources speak of ‘four tonnes’ – a figure that cannot be independently verified, however. Although there has been no official confirmation to date, it is very likely that these were weapons of war that were illegally transported on board the civilian aircraft and were intended for one (or more) of the civil war parties in Lebanon, but probably for the PLO, which was supported by Hungary. This is also supported by the fact that, according to informants from Hungary, the aircraft was parked in a particularly remote position at the airport that evening for boarding. For a period of around 15 minutes, the apron lighting in the vicinity of HA-LCI was even switched off – an absolutely unusual procedure. The authorities later spoke of a ‘power failure’ and denied that the lights had been switched off deliberately.

According to statements made by airport employees, several trucks arrived during this time window, from which the boxes containing the suspected military cargo were transferred to the Tupolev. This was also confirmed years later by Hungarian photographer Pál Geleta to a camera crew. He said he had seen the trucks arrive and the boxes being loaded himself. Such arms transports took place regularly at that time. Former Malév employees repeatedly confirmed this fact to journalists after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Lászlo Németh, the husband of flight attendant Lászlóné Németh, said during our personal meeting in Budapest in February 2024: "These illegal military transports did take place, that's not a rumour. The crews jokingly referred to the containers with the weapons as “flower boxes”." The full interview can be found in my book (German and English version) about Malev 240.

The weapons transports were also confirmed after the end of the Eastern Bloc by the airline's former chief pilot, András Fülöp. He stated that he himself had carried out several such transports. Fülöp died in 2008 at the age of 80. Today, a preserved Tu-154 B-2 (HA-LCA) at Budapest Airport bears his name.

Other state-owned airlines from countries under the influence of the Soviet Union also carried out such illegal transports on Moscow's orders, according to Hungarian aviation circles, which have been investigating the mystery surrounding flight Malév 240 for years. It is doubtful that the passengers were aware of these transports, as the Hungarians took great care to keep these matters as secret as possible. In an interview with Dutch journalists several years ago, contemporary witness Németh emphasised: ‘Malév was a semi-military airline that was involved in many secret operations.’

The arms deliveries were also confirmed in 2019 by Hungarian writer György Odze, who himself worked for Malév from 1970 to 1974, in an interview with a journalist from the Hungarian newspaper Népszava. He said: "We saw lorries coming to the aeroplane. The consignment note said “spare parts”. We simply called it the Kalashnikov Express."

Significant delay at take-off

Flight MA240 was scheduled to depart Budapest at 4:50 p.m. local time (2:50 p.m. UTC), but take-off was repeatedly delayed. The airline did not officially give a reason for this, even later on. Passengers even had to leave the Tupolev twice.

Today, it is considered certain that the delay was caused by waiting – in vain – for the arrival of the 53 PLO officials. During the night, the decision was finally made: flight MA240 was to take off at last, even without the Arab delegation. According to my research, the order came from the then Malév CEO Lénárt György himself. Like many other senior executives of the airline, he belonged to the MNVK-2 department of the Hungarian military intelligence service. At around 11:10 p.m. local time in Hungary (9:10 p.m. UTC, 12:10 a.m. local time in Beirut), the Tupolev finally took off from Budapest Airport and headed southeast.

Although the exact route can no longer be reconstructed with certainty, the crew probably took the shortest and most direct route, as there was hardly any air traffic at that time of day anyway. This route took them over Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey and Cyprus, which is only about 200 kilometres off the Lebanese coast and where British military units, including a radar surveillance unit, were stationed. The flight time from Budapest to Beirut was normally around three hours, depending on wind and weather conditions.

In the early hours of 30 September, at around 00:19 UTC (03:19 local time in Beirut), the pilots of flight MA 240 reported to air traffic control in Nicosia (Cyprus). This radio communication proceeded without incident. At that time, HA-LCI was flying at flight level 370 (37,000 feet, approximately 11,300 metres). Shortly afterwards, the air traffic controller cleared the Tupolev to descend. A little later, air traffic control in Nicosia instructed the crew of flight 240 to contact Beirut on frequency 119.3 MHz, which they did at 00:33 UTC. The controller in Beirut cleared the Malév to an altitude of 6,000 feet (approximately 1,800 metres).

However, the Beirut air traffic controller could not see the Hungarian aircraft on his radar. This was because the system had been out of order for some time as a result of the civil war. The airport's instrument landing system, or ILS for short, was also out of service. Captain Pintér and his first officer, Kvasz, therefore had to perform a visual approach. But such a manoeuvre was certainly no problem for the experienced crew, especially as the weather conditions that night were ideal. Visibility was more than 20 kilometres, the wind was light, the runway lights at Beirut were activated and the illuminated skyline of the city also guided the crew to the airport, which is located directly on the coast.

At 00:44 UTC (03:44 local time), the pilots of flight MA 240 informed Beirut air traffic control that they were passing flight level 190 (19,000 feet, approx. 5,800 metres). ‘Roger, report BOD outbound,’ replied the ground control. Approaching via the non-directional beacon (NDB) BOD, the Tupolev was guided to runway 17 (runway 16 since 2004). Flight MA240 was scheduled to reach the BOD beacon eight minutes later, at 00:52.

‘Roger, will do,’ came the reply from the Tupolev cockpit. That was the last radio contact with the aircraft – it never arrived in Beirut, but crashed shortly afterwards into the sea about eight to ten kilometres northeast of the airport off the coast. What happened next continues to preoccupy and outrage the Hungarian public to this day, half a century after the disaster, which has gone down in Hungarian aviation history as the most serious tragedy ever.

Cover-up and silence

After the Lebanese air traffic controller lost radio contact with the aircraft from Hungary, he first telephoned other air traffic control centres to ask whether the Tupolev might have landed in Cyprus, Syria or Turkey. However, all his enquiries were answered in the negative. Suspicions that MA240 had crashed grew stronger and stronger. Later, the air traffic controller on duty that night stated that there had been no signs of any problems during the last radio contact with MA240. Everything had been completely normal.

During a large-scale search operation involving ships from Lebanon and a Royal Air Force C-130 Hercules stationed in Cyprus, debris and individual bodies were finally discovered. But instead of immediately recovering the bodies and wreckage, as would be customary internationally, Hungary drew a veil of silence over the crash of its Tupolev.

Neither the wreckage nor the flight recorders were ever recovered, even though this would have been technically feasible – and still is today. Hungary even denied that any bodies had been found, even though Arab media reported on the recovery of victims and their burial, including photos. A passenger list or transcript of radio communications was also never published, and half a century after the crash, there is still no official investigation report – neither from Lebanon nor from Hungary.

Neither the wreckage nor the flight recorders were ever recovered, even though this would have been technically feasible – and still is today. Hungary even denied that any bodies had been found, even though Arab media reported on the recovery of victims and their burial, including photos. A passenger list or transcript of radio communications was also never published, and half a century after the crash, there is still no official investigation report – neither from Lebanon nor from Hungary.

Shooting down considered most likely cause of crash

Although the cause of the crash cannot be clarified beyond doubt, there are strong indications that the aircraft was shot down by an air-to-air missile, including the statement of a British soldier who was stationed at the RAF base in Cyprus at the time. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, several Malév employees also stated ‘off the record’ that Flight 240 had been ‘destroyed by an external force’, i.e. shot down. The most explicit statement came from former chief pilot András Fülöp: "The aircraft was hit by two missiles fired from a fighter jet. The air traffic controller told me this, but added that he was only telling me on a personal basis. If he is officially questioned about it, he will deny it. He has a family and does not want to get into a situation where he gets into trouble. That's it. And that's what I told our director."

Erkki Tuomioja, Finnish Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2000 to April 2007 and from 22 June 2011 to 29 May 2015, also believes the plane was shot down. In an interview, he said: ‘The plane crashed after being hit by a missile. The shooting down was an act of barbarism. We don't know who did it, but it is clear that the Palestinians booked on the flight were the target.’ Theoretically, several of the parties to the conflict at the time could have been responsible for the shooting down: Syria, Israel or Lebanon itself, for example. At the time, all three states had fighter jets (Israel: F-4 Phantom, Lebanon: Hawker Hunter, Mirage III, Syria: MiG 21, to name but a few) that would have been capable of doing so. And all three states would have benefited if the 53 PLO leaders believed to be on board had been killed in one fell swoop.

Hungary offered relatives ‘hush money’

In 2003, almost 30 years after the disaster, the democratic politician Miklós Csapody brought the issue back into the public eye in Hungary and asked the government whether, after almost three decades, a comprehensive investigation of the case and a recovery of the victims could finally be expected. In the same year, the Hungarian National Security Service (Nemzetbiztonsági Hivatal, NBH) produced two reports of its own on the crash of flight MA240. Among other things, these reports stated that the original documents relating to the accident were unfortunately no longer available. A year later, the Hungarian government set up a 100 million forint fund for the search and recovery of the wreckage, but once again took no further steps in this direction. When the NBH's 2003 reports were brought up again in public in 2007, the minister responsible for overseeing the security service stated that these two documents had been classified as ‘secret’. In 2009, the Hungarian government at the time finally contacted a professional international underwater salvage company and requested a cost estimate for the search and recovery of the remains of flight MA240. However, after the salvage company submitted its offer, the Hungarian government again took no action.

Instead, the money budgeted for the search and recovery of the wreck was used to compensate the Hungarian survivors. That was also in 2009. Those affected received 4,000,000 forints (equivalent to around 14,800 euros at the time) per person and, according to Lászlo Németh, had to sign a declaration in which they undertook not to make any further inquiries into the case and not to comment on it publicly. According to his own statements, Németh was the only one of the Hungarian relatives who did not accept the money and refused to sign this questionable agreement.

Relatives and friends of the victims want answers at last

In this form, the events surrounding Hungary's apparent obstruction of the investigation into the mysterious crash of Malév 240 can and must be described as unique in the history of modern commercial aviation. I am not aware of any other crash of this magnitude that has been investigated so superficially, if not to say virtually not at all. At the end of the day, it could simply be a matter of money. If, after recovering the wreckage of flight MA240, it turns out that the jet was indeed carrying illegal military goods on its irresponsible high-risk flight to a civil war zone and was shot down by a fighter jet belonging to one of the parties involved in the conflict, this could still cause a major international diplomatic scandal today, given the large number of foreign victims – and at the same time result in claims for damages amounting to millions of pounds against Hungary by the surviving relatives of the 60 passengers.

After all, Malév, which went bankrupt in 2012, was a state-owned airline at the time of the accident, which would make Hungary directly liable. It is even possible that the insurance company would attempt to recover the money paid out for the crashed Tupolev Tu-154A. Furthermore, based on the bullet holes in the wreckage of the Tu-154A, it might even be possible to prove which weapon system or calibre (Soviet or Western) was used to shoot down Flight 240.

And so it is hardly surprising that even people who are far from being conspiracy theorists sometimes get the feeling that – at least from the point of view of some Hungarian politicians – there are probably some very good reasons to leave the wreckage of the ill-fated HA-LCI resting in its watery grave at the bottom of the sea off the coast of Lebanon, so that it can never reveal its potentially highly explosive secrets to the Hungarian public.

The current military conflict in the Middle East, in which Israel is also fighting for its survival with the use of its air force, is another factor that is unlikely to make recovery of the wreckage any more likely. But hope springs eternal for the few surviving relatives, some of whom are commemorating the 50th anniversary of the disaster today at Aeropark Budapest.

Text: Patrick Huber